Research

My research projects tend to fall in the interesting intersection of oceanic fluid mechanics, computational science, and mathematics. More concretely, I enjoy the (often cyclical) work-flow of

- Devising / deriving physically meaningful mathematical diagnostics for analyzing ocean data

- Developing high-efficiency computer routines to implement those diagnostics

- Analyzing / interpreting / contextualizing the diagnostics to learn new things about the world’s oceans I primarily work in the field known as geophysical fluid dynamics, which studies the behaviour of fluid systems that are on scales large enough to be affected by the rotation of the Earth.

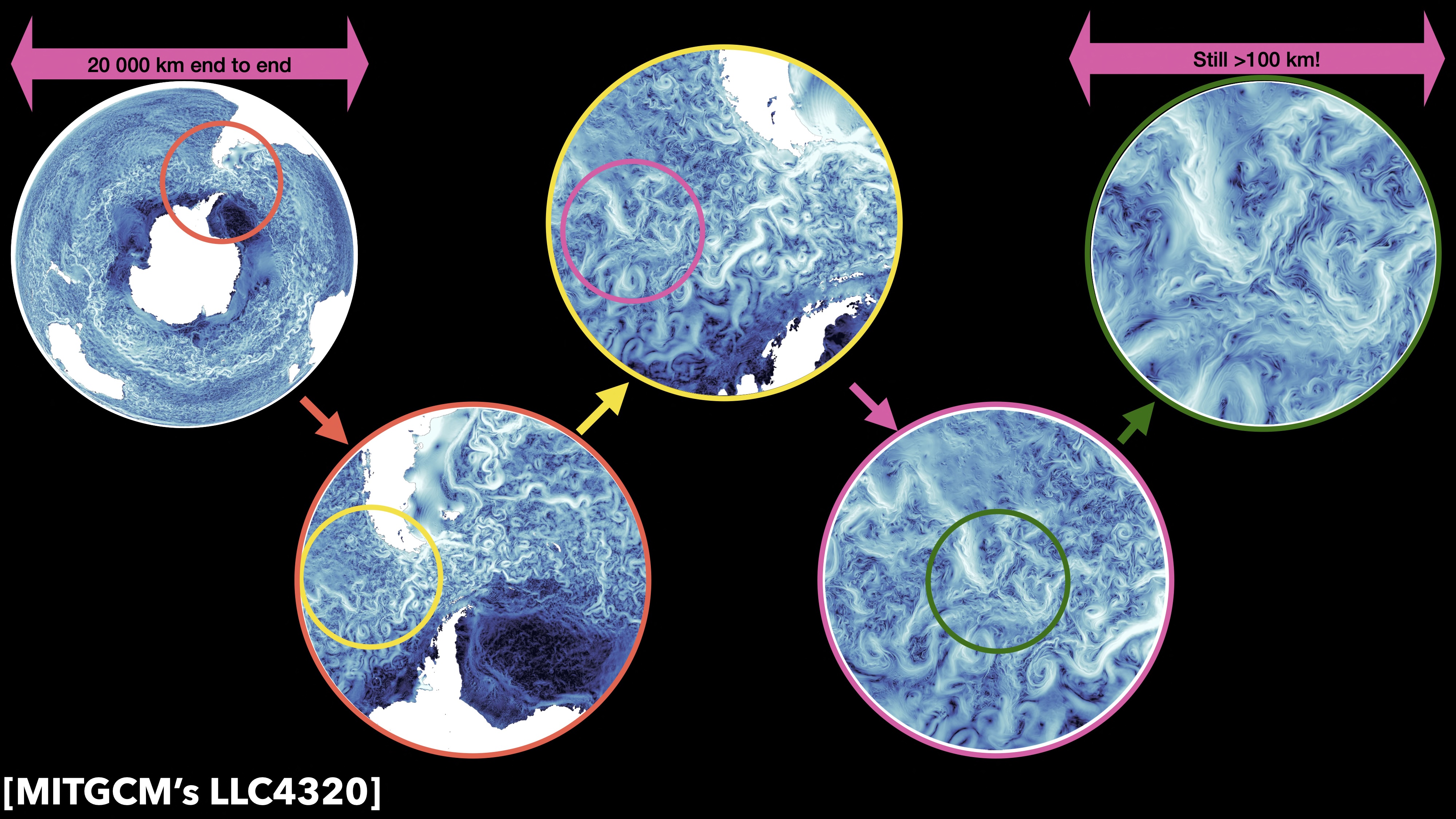

The world’s oceans are stunningly complex systems, full of features of varying size and character. At the sub-millimetre scale, viscosity dissipates enery to heat, while at scales of thousands of kilometres exists the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC), an ocean current system that surrounds the whole of Antarctica, and the equator-pole temperature gradient which drives massive circulation systems. Between those two extremes are ocean eddies (50 - 500 km) that account for the majority of oceanic kinetic energy, vertical transport arising from many mechanisms (subduction along front, wind-driven [Ekman] vertical transport, and eddy-induced), and many, many more.

Because of the non-linear physics involved, not only can there be energy across this whole range of length scales, but the differing scales can interact, causing energy to move between those scales, energizing some and weakening others.

Disentangling Large-scale Oceanic Flows

Traditional methods of studying energetics as a function of length scale, Fourier methods and spherical harmonics, don’t work well on global scales. Fourier methods require a periodic Cartesian geometry, and spherical harmonics are necessarily restricted to only analyzing global means, they cannot give space-local information.

I use a methodology called coarse-graining, which is a mathematically rigorous way of scale decomposing not only data, but also equations of motion – the physics – of the oceans. This allows us to quantify the physics of the ocean as a function of space, time, and length-scale.

Why is this important?

The oceans contain, receive, and emit enormous amounts of energy, and we need to know not only how much of that energy resides in features of different sizes, but also how that energy moves between those sizes. From a modeling perspective, despite the ever-increasing ability to conduct high-resolution simulations that resolve ocean eddies, resolving eddy scales in climate-scale simulations is still prohibitively expensive, and requires parameterization (or modeling) of physical processes at length-scales smaller than the grid resolution. Understanding and quantifying how those sub-grid processes impact resolved features, and understanding the energy pathways between wind, large-scale circulation, and eddy-scale flow, is necessary to develop more faithful models and improve our climate prediction capabilities.

Open-source Tool Development

I’m the lead developer of FlowSieve, a C++ library that provides tools for analyzing global oceanic and atmospheric data in mathematically rigorous and physically meaningful ways. FlowSieve was designed from the begininning to take advantage of high performance computing clusters, using both OpenMP and Open-MPI to provide optimized parallelization. FlowSieve continues to be developed, adding new diagnostic capabilities to continue expanding our ability to quantify the physics of the oceans and atmosphere.